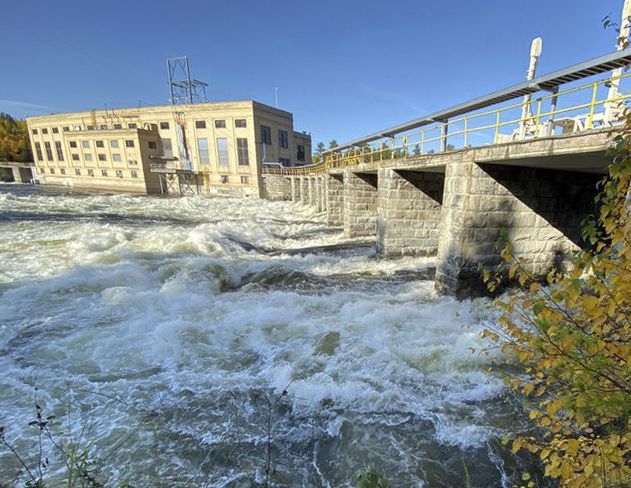

Due to extremely high fall flows in all local waterbodies, the Norman Dam was fully opened to 1,275 m3/s on Oct. 10.Given the very wet conditions throughout the watershed this fall, I thought I’d dedicate this week’s article to a discussion about water levels and how they are managed in this basin. While Mother Nature has the last word on how much water will be in the system, there are management mechanisms in place to help regulate levels as best they can, but with extreme conditions, like this fall, the impact of any human management can be reduced to almost nil in light of Mother Nature’s control.

Due to extremely high fall flows in all local waterbodies, the Norman Dam was fully opened to 1,275 m3/s on Oct. 10.Given the very wet conditions throughout the watershed this fall, I thought I’d dedicate this week’s article to a discussion about water levels and how they are managed in this basin. While Mother Nature has the last word on how much water will be in the system, there are management mechanisms in place to help regulate levels as best they can, but with extreme conditions, like this fall, the impact of any human management can be reduced to almost nil in light of Mother Nature’s control.

Following a relatively dry summer, rainfall in September and early October has set seasonal records in most areas across the Winnipeg River and English River basins. This has resulted in fast rising lake levels and river flows in the watershed. In some cases, the resulting flows are approaching records for this time of year.

Outflow from Rainy Lake into Rainy River is four times greater than normal for early October. This is contributing less than half of the extremely high inflow to Lake of the Woods, the remainder largely coming from direct rainfall around the lake over the past few weeks. Under normal conditions, the water from Rainy Lake and the Rainy River contributes two-thirds of the water entering Lake of the Woods, so this is a dynamic that significantly alters regular management scenarios.

When it comes to how water is managed in the greater Rainy-Lake of the Woods watershed, let’s talk about the three entities at play and the mechanisms by which they regulate water levels. First, in the central part of the watershed, water flowing out of Namakan and Rainy Lakes into the Rainy River has been controlled by dams for more than 100 years. Since 1949, Canada and the U.S., through the International Joint Commission, have jointly established formal rules for regulating water levels and flows for the two lakes. These “rule curves” set target ranges for the lake levels every day of the year and have been modified over time to better consider the needs of the ecosystem and varied interests. The target ranges or “bands” are not static, they fluctuate with the season.

Moving further downstream, the Lake of the Woods Control Board (LWCB) manages the waters of Lake of the Woods, Lac Seul, and the Winnipeg and English Rivers. It was formed in 1919 and operates under Canadian federal and provincial legislation and a Canada-United States Treaty. Instead of managing within a rule curve, the LWCB manages the lake level between a static low and high elevation, as stipulated in the Treaty. When conditions are extreme (i.e. if levels rise above or fall below those static elevations), the International Lake of the Woods Control Board steps in – this Board was also created by the Treaty.

The communication between these three entities is constant and, in fact, served by a common Secretariat that consists of a team of water resource engineers extremely familiar with the workings of this basin. How does this happen when the engineers don’t work right here in the watershed? The LWCB regularly measures water levels at strategic points, gathers weather information and monitors outflow from the basin’s outlets. Through state-of-the-art monitoring and satellite link-ups, these data – more than 6,000 pieces each week – are brought together and professionally analyzed in the interest of the basin’s users.

With water levels what they are and winter around the corner, shoreline property owners are advised to take precautionary steps for what spring may bring.

This series is provided as part of the International Watershed Coordination Program of the Lake of the Woods Water Sustainability Foundation.

Kelli Saunders, M.Sc., is the International Watershed Coordinator with the Lake of the Woods Water Sustainability Foundation.