This article was originally written by Greg Seitz in 2015 for Field Notes -Stories from the St. Croix Watershed Research Station of the Science Museum of Minnesota; it is used here with permission of the SCWRS. Follow up work to these studies is underway

Long, bumpy boat rides are a fundamental part of finding the clues to Lake of the Woods’ water quality problems. The huge lake on the Canada-U.S.A. border requires speeding long distances over rough water to remote sites, but the trips have been worth it. After several years of study by research station scientists, the questions have evolved from why does the massive lake get huge toxic algae blooms? and can we do anything about it? to what lake conditions lead to these blooms? and where are the nutrients, which fuel the blooms, coming from?

Emerging explanations to the latter questions could help solve the first two.

This summer, station scientists have sought those answers by deploying custom buoys in the southern half of the lake to continuously collect information about key weather and water conditions. In July, the scientists collected the first month’s data, almost immediately gaining insights into problems plaguing Lake of the Woods. They just had to cross miles of open water to do it.

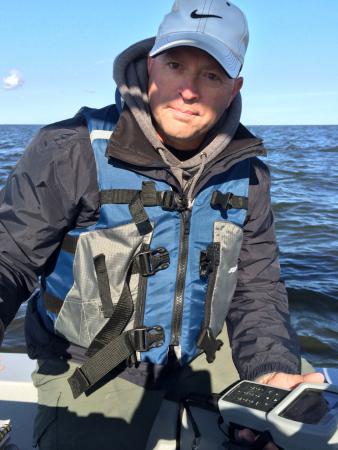

Lake of the Woods has a 60-mile fetch for the wind to whip across, and it can push some big waves. That makes work and travel dependent on the skies, and could play a key role in the lake’s algae problem. The lake was passable in July when the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency’s Cary Hernandez piloted station scientists Mark Edlund and Adam Heathcote across 20-mile stretches of open water, the boat often slamming off four-foot rollers as they motored for hours across the inland sea.

“It’s not a good idea to plan to do anything physical the day after that,” Heathcote says.

As I wrote about earlier this year, the station’s Lake of the Woods study is trying to determine why, despite significant reductions in the amount of nutrients flowing into the lake, it still experiences massive algae blooms. After the Clean Water Act was passed in 1972, paper mills on the Rainy River (the lake’s largest tributary) drastically cut the amount of waste they were dumping in the water, while communities have improved their sewer systems.

But the lake keeps getting greener.

Using sediment cores and other techniques, station scientists previously reconstructed the history of the lake and the factors that affect its water, nutrient levels, and sediment. They studied satellite imagery and ice-out records. Climate change was an obvious factor, because the northern part of the lake is now seeing four more weeks of ice-free conditions each year than it did decades ago, and a longer open water season means a longer growing season.

But it didn’t totally make sense, because the algae blooms were worse on the southern part, where ice-out has remained relatively stable. And it still didn’t explain why algae would get worse while nutrient inputs declined.

Perhaps, somehow, the phosphorus that had entered the lake during the paper and population booms of the mid-twentieth century is being recycled. Nitrogen and phosphorus, algae’s favorite food, should be quickly buried by inches of mud, but it could be that Lake of the Woods’ turbulent waters are combining with short periods of temperature stratification (when the cold bottom waters of a lake do not mix with the warmer water above) to deplete oxygen and draw nutrients from the sediments. Particularly windy days then mix nutrient rich particles of sediment throughout the water column, allowing pollution from many years ago to be reused over and over again.

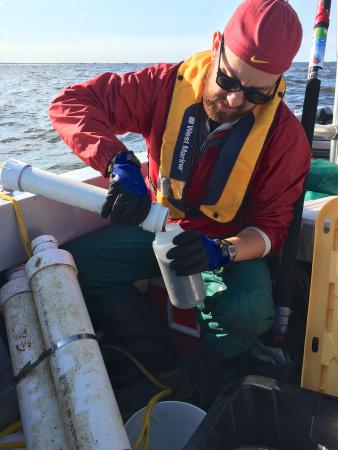

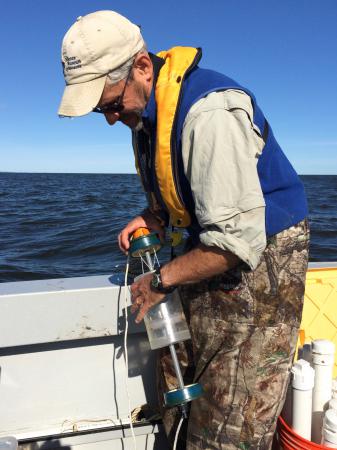

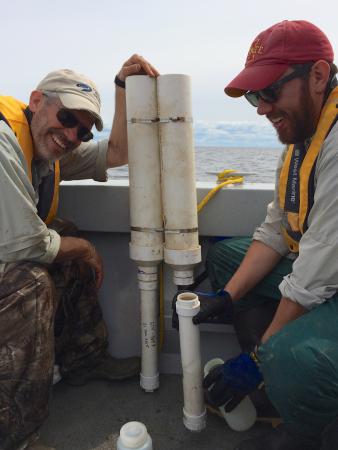

To test the idea, the team manufactured buoys that could be left in the lake to identify conditions that might explain the conundrum. Anchored below the surface in Muskeg and Big Traverse bays, the devices continuously monitor water temperature and dissolved oxygen content, as well as collect sediment that was suspended in the water. The scientists hoped the instruments could survive a few months in the lake, and that they could find them and retrieve the logged data. They went to great lengths to ensure the buoys didn’t drift away and disappear, including using nearly 90 pounds of anchor.

When the scientists went back a month after deploying the buoys, they were first relieved to quickly find them. Then they were encouraged by what they found in the 43,000 data points they downloaded.

The minute-by-minute changes in temperature and chemistry were processed and analyzed, and confirmed that the southern part of the lake had indeed stratified twice in the previous four weeks. This meant colder water collected on the bottom, where its oxygen was rapidly depleted. This happens in many lakes, and it can often exacerbate algae problems. The lower-oxygen water just above the bottom of the lake absorbs nutrients coming out of the sediment much faster than oxygen-rich water. By combining the data from the buoys with meteorological information, it became clear that when the winds blow, this nutrient-rich bottom water can mix together with the warmer water above where, when exposed to light, it can feed new algae.

It remains to be seen whether or not this correlates to the short-lived blooms of blue-green algae. Last week, the scientists were back on Lake of the Woods, collecting another month of data, seeking to solve the mysteries of its waters, and crisscrossing its windy surface.

The bouncy trip onto the lake in July also provided a reminder of the urgency of the study and the need to understand the problem: blue-green algae were already apparent in areas.