Reduce the toxic chemicals in your house – what goes down your drain eventually goes to the nearest waterbody, whether its via the sewage treatment plant or a storm drain on your street or your own septic system. Try to transition from harsh chemicals to more natural products – baking soda and vinegar have great cleaning power!

The International Watershed Coordinator—Keeping Us Working Together.

Meghan Mills is the Foundation's International Watershed Coordinator, a dedicated resource to support and coordinate research, management and civic engagement initiatives underway internationally across our watershed. Meg focuses on working together with four main spheres of activity in the watershed:

Meghan Mills is the Foundation's International Watershed Coordinator, a dedicated resource to support and coordinate research, management and civic engagement initiatives underway internationally across our watershed. Meg focuses on working together with four main spheres of activity in the watershed:

- International Joint Commission (IJC) and its International Rainy-Lake of the Woods Watershed Board (IRLWWB)

- The International Multi Agency Arrangement (IMA) research and management collaboration.'

- Indigenous Nations

- Local groups and agencies engaged in watershed activities throughout the bi-national basin.

- Details

Originally published in Kenora Miner and News on November 13, 2019

This week’s article features the fourth and final installment on the Canadian science program. In past articles, I’ve talked about algae and how it forms, but this week, I’m reporting on some of the work Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) has been doing to dig a bit deeper into the main drivers of blooms. Thanks goes out to Arthur Zastepa and Dale Van Stempvoort of ECCC for this update.

This week’s article features the fourth and final installment on the Canadian science program. In past articles, I’ve talked about algae and how it forms, but this week, I’m reporting on some of the work Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) has been doing to dig a bit deeper into the main drivers of blooms. Thanks goes out to Arthur Zastepa and Dale Van Stempvoort of ECCC for this update.

Phytoplankton form the base of the food web, converting solar energy into chemical energy (i.e. food) and generating oxygen as part of the process called photosynthesis. Under the right conditions, phytoplankton may grow out of control, causing dramatic changes in water quality and visible surface scums. Referred to generically as “harmful cyanobacterial and algal blooms,” the decaying cell material consumes oxygen in the water and creates the undesirable sights and smells we see along shorelines or in open water. Some species can produce toxins harmful to humans and wildlife and taste and odour compounds that foul drinking and recreational water.

- Details

Originally published in Kenora Miner and News on November 6, 2019

We tend to hear more and more concern about invasive species, but what are they and how can we help prevent their spread? An invasive species is one that is not native to a specific location (an introduced species), and that has a tendency to spread to a degree believed to cause damage to the environment, economy or human health.

We tend to hear more and more concern about invasive species, but what are they and how can we help prevent their spread? An invasive species is one that is not native to a specific location (an introduced species), and that has a tendency to spread to a degree believed to cause damage to the environment, economy or human health.

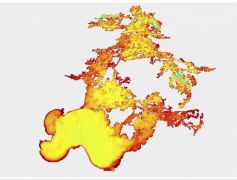

The Rainy-Lake of the Woods watershed is vulnerable to introductions of non-native species, aquatic ones in particular, due to its proximity to several large water bodies and systems (i.e. Great Lakes, Mississippi drainage system, Red River) and its popularity as a tourist destination.

- Details

Originally published in Kenora Miner and News on October 30, 2019

Environment Canada’s science program: Part Three

Environment Canada’s science program: Part Three

This week, I’m circling back to Canada’s science in the watershed – so far, I’ve touched on Environment and Climate Change Canada’s (ECCC) satellite and baseline monitoring initiatives. Today, the focus is on ‘modelling’ – essentially, trying to predict water quality conditions in the basin under various scenarios. Thanks goes out to one of the lead scientists on this, Reza Valipour, who has provided this update.

This project aims to develop an integrated model for U.S. and Canadian waters that flow into Lake of the Woods that can predict water movements and water quality. The model will build a connection between the land and water to better understand the cause and effect of algal blooms. It will determine the effectiveness of risk reduction strategies on water quality in Lake of the Woods and help predict the lake’s response to climate change.

- Details

Originally published in Kenora Miner and News on October 18, 2019

Given the very wet conditions throughout the watershed this fall, I thought I’d dedicate this week’s article to a discussion about water levels and how they are managed in this basin. While Mother Nature has the last word on how much water will be in the system, there are management mechanisms in place to help regulate levels as best they can, but with extreme conditions, like this fall, the impact of any human management can be reduced to almost nil in light of Mother Nature’s control.

Given the very wet conditions throughout the watershed this fall, I thought I’d dedicate this week’s article to a discussion about water levels and how they are managed in this basin. While Mother Nature has the last word on how much water will be in the system, there are management mechanisms in place to help regulate levels as best they can, but with extreme conditions, like this fall, the impact of any human management can be reduced to almost nil in light of Mother Nature’s control.

Following a relatively dry summer, rainfall in September and early October has set seasonal records in most areas across the Winnipeg River and English River basins. This has resulted in fast rising lake levels and river flows in the watershed. In some cases, the resulting flows are approaching records for this time of year.

- Details

Originally published in Kenora Miner and News on October 9, 2019

Last week, I introduced some of the work that Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) is doing in the Rainy – Lake of the Woods basin to provide a bit of an overview of the program with a focus on its satellite algae-tracking project. This week, the focus is on the baseline monitoring that ECCC has been doing over the course of the past 10 years.

Last week, I introduced some of the work that Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) is doing in the Rainy – Lake of the Woods basin to provide a bit of an overview of the program with a focus on its satellite algae-tracking project. This week, the focus is on the baseline monitoring that ECCC has been doing over the course of the past 10 years.

Since 2009, ECCC has been conducting two main baseline monitoring projects. One is collecting water quality information at 25-30 stations throughout Lake of the Woods in the spring and late summer, and the second at four key points along the Rainy River; biweekly in the ice-free period, and monthly through the ice. At these sites, ECCC is measuring nutrients, trace metals, sediment chemistry, and biological indicators that help to understand ecosystem health (chlorophyll-a, benthic invertebrates). ECCC also used to monitor mercury in water in the Rainy River, but samples were routinely below detection levels or below established guidelines, so they no longer monitor it.

- Details

Originally published in Kenora Miner and News on October 3, 2019

A few weeks ago, I outlined the work that Minnesota is doing to understand water quality on Lake of the Woods through its Total Maximum Daily Load study. Over the next few weeks, I will highlight the work on the other side of the border being done by Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC).

A few weeks ago, I outlined the work that Minnesota is doing to understand water quality on Lake of the Woods through its Total Maximum Daily Load study. Over the next few weeks, I will highlight the work on the other side of the border being done by Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC).

For the past three and a half years, ECCC has been conducting integrated research and monitoring to get a handle on water quality conditions and algal blooms. This has included projects such as the development of satellite tools to identify and monitor blooms; research into the status, trends and drivers of algae blooms; measuring nutrient inputs from shoreline developments; developing a model to help determine the effectiveness of nutrient reduction strategies on the water quality in Lake of the Woods; and, predicting the lake’s response to climate change. They have been collaborating with other agencies who are also doing research in this basin.

- Details

Originally published in Kenora Miner and News on September 25, 2019

Last week, I introduced the idea that we can all make a difference when it comes to protecting our watershed and, collectively, that can have a huge impact. This week, I am continuing that conversation with a few additional ideas that are easy to do and are relevant whether you own waterfront property or not.

Last week, I introduced the idea that we can all make a difference when it comes to protecting our watershed and, collectively, that can have a huge impact. This week, I am continuing that conversation with a few additional ideas that are easy to do and are relevant whether you own waterfront property or not.

- Details

Originally published in Kenora Miner and News on September 18, 2019.

The short answer is YES. Reducing impacts on our environment has to be a collective initiative and every single person and the changes they make will have an impact. In past articles, I’ve focused on what agencies are doing to understand watershed issues and work towards protection. Today and next week, I’ll focus on ideas that we, as watershed citizens, can all do.

The short answer is YES. Reducing impacts on our environment has to be a collective initiative and every single person and the changes they make will have an impact. In past articles, I’ve focused on what agencies are doing to understand watershed issues and work towards protection. Today and next week, I’ll focus on ideas that we, as watershed citizens, can all do.

One of the common concerns I hear is whether septic systems are having an impact on water quality. If not properly maintained, septic systems can pollute the lake with phosphates and bacteria. Grease, oils, harsh cleaners and supposedly “disposable” personal products can really stress out a septic system, clog it up and reduce its efficiency. Follow this mantra: “If in doubt, don’t pour it out”. A septic system needs regular check ups and pump outs and needs to be large enough in size for the home it is servicing.

- Details

Originally published in Kenora Miner and News on September 4, 2019

Last week, I mentioned that there are three components to the International Watershed Coordination Program here in our basin, one of them being the “local” or grassroots component. This is where you come in. Protecting water quality is everyone’s responsibility, but how does an individual find a way to make a difference? Let me offer a few ideas based on the civic engagement work we do with our partners.

Last week, I mentioned that there are three components to the International Watershed Coordination Program here in our basin, one of them being the “local” or grassroots component. This is where you come in. Protecting water quality is everyone’s responsibility, but how does an individual find a way to make a difference? Let me offer a few ideas based on the civic engagement work we do with our partners.

We are so fortunate to have over 40 lake associations in this watershed, most are in Minnesota, but the largest in Ontario is right here. The Lake of the Woods District Stewardship Association (LOWDSA) has been promoting good water stewardship for over 50 years and absolutely anyone – not just waterfront residents – can be a member. They have a strong environmental focus and we partner with them regularly. For the past three summers, for example, LOWDSA has been a key partner in our cross-border drain stencil project working with children in the community to paint the message “A Healthy Lake Starts Here” or “Dump No Waste” beside storm drains, to date, well over 300 drains have been painted in three communities, reminding us that only rain should go down the drain, because these drains direct runoff directly to our nearby waterbodies. As a way to support the many lake associations in the basin, we also host an annual Lake Association Network event, bringing together like-minded individuals who are motivating their members to be good stewards in a wide variety of ways.

- Details

Originally published in Kenora Miner and News on August 28, 2019

About eight years ago, with coworkers aboard a boat on Rainy Lake, ideas were brewing around the need to somehow coordinate and harness the energy and dedication of individuals working on water issues in this basin and break down communication barriers. Not long after, the concept of establishing an international watershed coordination program was born – a program that would be supported by partners, for partners. My position as International Watershed Coordinator began, with a focus on three levels of integration that, together, make up the International Watershed Coordination Program (IWCP): international, regional and local. Over the years, the Lake of the Woods Water Sustainability Foundation has steered this ship by contributing as a funding partner and facilitator, with our long standing partners from south of the border, the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency and Koochiching Soil and Water Conservation District. Along the way, the province of Manitoba has contributed and, currently, our partners include the International Joint Commission (IJC) and Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC).

About eight years ago, with coworkers aboard a boat on Rainy Lake, ideas were brewing around the need to somehow coordinate and harness the energy and dedication of individuals working on water issues in this basin and break down communication barriers. Not long after, the concept of establishing an international watershed coordination program was born – a program that would be supported by partners, for partners. My position as International Watershed Coordinator began, with a focus on three levels of integration that, together, make up the International Watershed Coordination Program (IWCP): international, regional and local. Over the years, the Lake of the Woods Water Sustainability Foundation has steered this ship by contributing as a funding partner and facilitator, with our long standing partners from south of the border, the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency and Koochiching Soil and Water Conservation District. Along the way, the province of Manitoba has contributed and, currently, our partners include the International Joint Commission (IJC) and Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC).