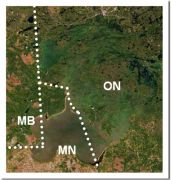

The view from space is compelling. Each summer, Lake of the Woods is plagued by blue green algae blooms, as can be seen in the satellite image pictured above. It’s a transboundary lake – provincially and internationally – and that means that we must cooperate closely with our neighbors in Manitoba and the U.S. to protect our shared waters. This is the reason we have the International Joint Commission, or IJC, and its Rainy-Lake of the Woods Watershed Board, with a mandate to monitor ecosystem health across the border. So, how do you protect water quality when the water crosses multiple boundaries?

The view from space is compelling. Each summer, Lake of the Woods is plagued by blue green algae blooms, as can be seen in the satellite image pictured above. It’s a transboundary lake – provincially and internationally – and that means that we must cooperate closely with our neighbors in Manitoba and the U.S. to protect our shared waters. This is the reason we have the International Joint Commission, or IJC, and its Rainy-Lake of the Woods Watershed Board, with a mandate to monitor ecosystem health across the border. So, how do you protect water quality when the water crosses multiple boundaries?

The International Watershed Coordinator—Keeping Us Working Together.

Meghan Mills is the Foundation's International Watershed Coordinator, a dedicated resource to support and coordinate research, management and civic engagement initiatives underway internationally across our watershed. Meg focuses on working together with four main spheres of activity in the watershed:

Meghan Mills is the Foundation's International Watershed Coordinator, a dedicated resource to support and coordinate research, management and civic engagement initiatives underway internationally across our watershed. Meg focuses on working together with four main spheres of activity in the watershed:

- International Joint Commission (IJC) and its International Rainy-Lake of the Woods Watershed Board (IRLWWB)

- The International Multi Agency Arrangement (IMA) research and management collaboration.'

- Indigenous Nations

- Local groups and agencies engaged in watershed activities throughout the bi-national basin.

- Details

Originally published in Kenora Miner and News on August 20, 2019

Several of the articles i n this column have focused on water quality issues. Today, I’ll focus on the successful cooperation that has grown over the last decade between governments, our Foundation, the International Joint Commission (IJC) and other partners to work together to understand the issues and find solutions. You’ll get a sense that there is great communication across the border – this is fairly unique. Since the watershed is shared between two provinces, one state and two countries, you can well imagine that there are many players; in fact, there are over 27 agencies with some form of water quality mandate in this watershed. As Watershed Coordinator, my role is to help keep the lines of communication open amongst all these players, help align priorities and ensure partnerships are forged wherever possible. I have to say, the dedication and passion of the people I work with in both countries makes my job very rewarding! More on that in a future article.

n this column have focused on water quality issues. Today, I’ll focus on the successful cooperation that has grown over the last decade between governments, our Foundation, the International Joint Commission (IJC) and other partners to work together to understand the issues and find solutions. You’ll get a sense that there is great communication across the border – this is fairly unique. Since the watershed is shared between two provinces, one state and two countries, you can well imagine that there are many players; in fact, there are over 27 agencies with some form of water quality mandate in this watershed. As Watershed Coordinator, my role is to help keep the lines of communication open amongst all these players, help align priorities and ensure partnerships are forged wherever possible. I have to say, the dedication and passion of the people I work with in both countries makes my job very rewarding! More on that in a future article.

- Details

Originally published in Kenora Miner and News on August 13, 2019

The last few articles have focused on nutrients and algal blooms, given that they are of concern on Lake of the Woods and other lakes in the watershed. But, as noted in previous articles, there are other environmental issues we should all be aware of – some are more concentrated in upstream areas, some are more widespread. I will touch briefly on each.

The last few articles have focused on nutrients and algal blooms, given that they are of concern on Lake of the Woods and other lakes in the watershed. But, as noted in previous articles, there are other environmental issues we should all be aware of – some are more concentrated in upstream areas, some are more widespread. I will touch briefly on each.

Contaminants are generally less of a concern here than in other more populated areas, like the Great Lakes. Nevertheless, they can enter the surface and groundwater from what are called “point source discharges” like wastewater treatment plants, stormwater drains, industrial outfalls and more diffuse, “non-point sources” like runoff from agricultural fields or septic systems.The point source discharges are controlled through regulations, but diffuse sources are harder to monitor and manage.

- Details

Originally published in Kenora Miner and News on July 26, 2019

For those of us living at the north end of Lake of the Woods, the Rainy River is a two hour car drive away and perhaps not familiar to us, but this river is the most influential tributary to Lake of the Woods, contributing about 70 per cent of the total water flowing into the lake. This week, we take a look at a bit of the fascinating history of the cleanup of the Rainy River – which has had a direct impact on the health of Lake of the Woods.

- Details

Originally published in Kenora Miner and News on July 31, 2019

Last week, I discussed the impressive cleanup of the Rainy River, including substantial reductions in phosphorus from the paper mills, sewage treatment plants and other sources in the past several decades. The question I left you with was, if phosphorus was reduced, why are we still getting algae blooms?

- Details

Originally publishe d in Kenora Miner and News on August 7, 2019

d in Kenora Miner and News on August 7, 2019

Algae are microscopic, plant-like organisms that can occur naturally in ponds, rivers, lakes and streams. Although they can be olive-green, red or black, depending on the species, the blue-green version most of us are familiar with are actually a group of bacteria, called cyanobacteria. In the Rainy-Lake of the Woods watershed, algae have been around for years and, in fact, explorers, fur traders and settlers reported them 200 years ago. Algae thrive on the nutrients (mainly phosphorus in this part of the country) in the water – some is natural and some is human-caused, like agricultural and stormwater runoff or leaching from septic systems. In some cases, where nutrients are excessive, the algae can grow to the point where they combine and form a bloom or a surface scum.

- Details

Originally published in Kenora Miner and News on July 18, 2019

Last week, I outlined what a “watershed” is and described the geography of ours – the Rainy-Lake of the Woods Watershed. It is huge and diverse, so it goes without saying that the environmental issues are just as diverse.

Last week, I outlined what a “watershed” is and described the geography of ours – the Rainy-Lake of the Woods Watershed. It is huge and diverse, so it goes without saying that the environmental issues are just as diverse.

Low populations, fairly low industrial impacts, lots of forest cover and water all make for a generally healthy watershed. But over the years as more attention turned towards ecosystem health, it became clear that there are, indeed, environmental stresses here and what is a stress on Lake of the Woods is not necessarily a stress upstream. Let’s go on a tour of the watershed from east to west and see how the issues differ as we move downstream.

- Details

Originally published in the Kenora Miner and News on: June 28, 2019

- Details

Originally published in the Kenora Miner and News on: July 10, 2019

The Rainy-Lake of the Woods Watershed is 69,750 sq. km, roughly 400 km east to west and 260 km north to south. About 41 per cent of the watershed is in the U.S. and 59 per cent is in Canada. If you’ve travelled to Atikokan or Upsala in Ontario or Ely or Cook in Minnesota, you were still in our watershed. If you’ve paddled the Turtle River in Ontario or fished in Vermilion Lake in Minnesota, you were still in our watershed. Approximately 14 per cent of the watershed is open water; where there is land, 93 per cent is covered by forest or grassland, and much of that is within provincial parks and national forests. Only 6.4 per cent of the landbase is agricultural, mostly found in the lower Rainy River area.

The Rainy-Lake of the Woods Watershed is 69,750 sq. km, roughly 400 km east to west and 260 km north to south. About 41 per cent of the watershed is in the U.S. and 59 per cent is in Canada. If you’ve travelled to Atikokan or Upsala in Ontario or Ely or Cook in Minnesota, you were still in our watershed. If you’ve paddled the Turtle River in Ontario or fished in Vermilion Lake in Minnesota, you were still in our watershed. Approximately 14 per cent of the watershed is open water; where there is land, 93 per cent is covered by forest or grassland, and much of that is within provincial parks and national forests. Only 6.4 per cent of the landbase is agricultural, mostly found in the lower Rainy River area.

- Details

Originally published in the Kenora Miner and News on: June 24, 2019

Water…it gives us life, it symbolizes summer, it has spiritual meaning, it calms us, it’s what defines our community. To celebrate the importance of water locally and the great efforts collectively to protect it, this column will be dedicated to water throughout the summer months – its quality, its governance, its future and how we can all help to preserve it.

Water…it gives us life, it symbolizes summer, it has spiritual meaning, it calms us, it’s what defines our community. To celebrate the importance of water locally and the great efforts collectively to protect it, this column will be dedicated to water throughout the summer months – its quality, its governance, its future and how we can all help to preserve it.

Here in Kenora, we are at the downstream end of the vast Rainy-Lake of the Woods watershed – 69,750 sq.km in size, the size of New Brunswick! We share our water with Minnesota and Manitoba – it is an international treasure, providing drinking water to over three quarters of a million people. What happens upstream impacts what happens downstream and this is why we need to work together with our neighbours on research and on a plan with actions to protect our water.